My knowledge of the Orcutt family’s trek from Kansas to Washington Territory comes from memoirs written by Rosella Orcutt, my first cousin three times removed, and my great uncle, Joseph Morris. Rosella was actually a passenger on that journey, although only three years old at the time, and my great uncle Joe hadn’t even been born when his mother migrated west. Rosella and Joe really just documented the stories told to them by older members of the wagon train and for that reason my research has been an attempt to verify what they wrote.

—————————————————————————–

When word was received from Clarenda in the fall of 1881about their mother’s failing health, three Orcutt sons and a daughter decided to leave Kansas and hurry to the Northwest.

While they were in a hurry, this wasn’t a spur of the moment decision. For years powerful business interests had been promoting opportunities in Washington Territory to potential settlers – not the least of those interests was Wall Street financier, Jay Cooke, who was selling railroad bonds to build the Northern Pacific Railroad and conect the Great Lakes with the Pacific Northwest. Cooke needed to build excitement about the Pacific Northwest to sell his bonds, so he hired Ezra Meeker, a hop grower from the Puyallup Valley in Washington, to promote the mild climate and available land to families like the Orcutt’s … and it worked. First Clarenda and her husband came west in 1879 because Delos had landed a job working on the Northern Pacific, and then two years later Daniel and Pamelia Orcutt followed, hoping the climate would be beneficial to Pamelia’s deteriorating health. The following year four more Orcutt families sold their Kansas holdings and migrated west.

In her memoir, Rosella described how her father (Alvin Orcutt) “sold his farm and stock, keeping four good horses and two wagons. One wagon he fixed up real nice just for a cook wagon. The other carried the family’s beds and trunks full of clothing and other belongings”.

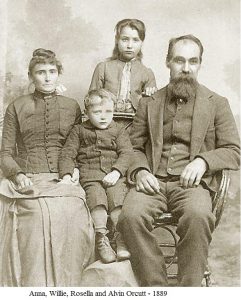

Alvin, Anna, Rosella and Willie, 1889

Rosella wrote “on a bright May morning in 1882 my father, mother, my two brothers, a sister and me, took our last look at our little house on the prairie and started the long journey

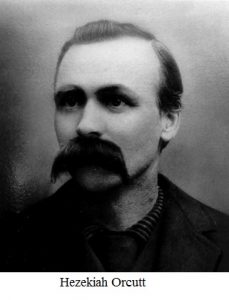

west. Father’s two brothers, Darwin and Hezekiah and their families and several neighbors made up our wagon train.”

I find it interesting Rosella did not mention by name my great-great grandparents, Tom and Mary Jane Pixley. Instead she categorized the Pixley’s into a crowd referred to as “neighbors”. It’s true, Tom and Mary Jane had been neighbors, but Mary Jane was also Alvin’s sister and Rosella’s aunt and certainly warranted a mention just like uncles Darwin and Hezekiah. I later found there was some kind of falling out between the Pixley and Orcutt families, so little Rosella may not have known Mary Jane was her aunt and, in fairness, the Pixley’s never mentioned the Orcutt’s either. I don’t believe my Uncle Joe even knew about his uncles Alvin, Darwin or Hezekiah, because they were never mentioned in his memoir.

Rosella’s story continued, “After a month or so a man’s wife got sick with a fever and as the days wore on she got real bad. Her husband thought if we would stop and make camp for a few days it might help her. The older children were getting pretty tired of walking by then and were glad to stay in one place long enough to build tiny houses and fences out of rocks and just play.”

Rosella’s story continued, “After a month or so a man’s wife got sick with a fever and as the days wore on she got real bad. Her husband thought if we would stop and make camp for a few days it might help her. The older children were getting pretty tired of walking by then and were glad to stay in one place long enough to build tiny houses and fences out of rocks and just play.”

Joe Morris wrote how the children walked barefoot behind the wagons because they couldn’t afford to wear out their shoes. He said the soles of their feet became so calloused they could step on a sharp stone and not feel it. His mother told him how she accidentally walked across hot coals from the previous night’s fire and didn’t even burn the bottoms of her feet.

While the children were happy to stop and play, the adults must have been worried. Rosella doesn’t specifically identify the “fever”, but the primary killer on the Oregon Trail was cholera, which was likely a death sentence and could quickly spread to others in the company.

Rosella said “everyone helped all they could, but the Lord had his way and took her home. She was buried by the roadside and a fire was made over her grave and when nothing but black coals were left each of the wagons was driven over the coals so as to erase all traces of her grave so the Indians wouldn’t find it and disturb her last resting place.”

Sickness dogged the Orcutt wagon train. Rosella wrote how “one morning mother didn’t feel so good but she took care of us wee ones and got breakfast ready and then put the cook wagon in shape. By afternoon she was too sick with the Mountain Fever to drive a wagon or care for us younger children.”

Rosella related how her mother, Anna, was sick for days, but urged the wagons to keep going. Anna’s sixteen year old son, Dan, took over caring for the younger children while ten year old Jake drove one wagon and their father, Alvin, drove the other. Alvin doctored his wife at night from his medicine box, which Rosella said contained quinine, niter, opium and brandy. Anna survived, but Rosella did tell in her memoir of how her mother was sickly for the rest of her life. (I checked various online medical journals to identify Anna’s fever – those journals speculated the disease called “Mountain Fever” was either typhoid fever or an insect-borne disease like Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Either disease was serious and proved fatal to those on the trail about 30% of the time.)

There were other challenges that made the journey long and arduous. Rosella told of “mire holes”, created by heavy rains that trapped and damaged the wagons in the mud, and how general wear and tear broke the wagons down, slowing progress. Her father brought along his blacksmith tools and kept busy repairing broken wheels and harnesses to keep the train moving, but when they reached the mountains one of her father’s wagons broke too badly to be repaired and so they “took what they could and left everything else along the trail”. Rosella described her mother’s grit by saying she didn’t mind so much losing the wagon because “it made for less things to worry about”.

Worries facing the company were varied; Rosella told how her father brought along four milk cows and they would often stray, delaying the train while the cows were rounded up. Joe Morris wrote about a time when an Indian approached the train and asked for food or “whatever else would be offered”. His mother said the Indian was “friendly, but his face was painted and that made the adults very nervous because they heard tales of Indian massacres”.

Crossing rivers brought their own problems. Lead riders looked for a shallow ford where the animals could wade across, pulling the wagons. Rosella told a story about one such crossing when her brother Jake feared the water would be too swift and deep, so he tied himself to his horse. Half way across the horse stumbled and fell and as the animal struggled to get up Jake was trapped underneath the water by the rope. His older brother saw what happened and got to him quickly, cutting the rope and pulling Jake to the surface. When he could talk Jake said “I was thirsty, but not that thirsty”.

Sometimes the water was too deep to wade and it became necessary to build rafts to float the wagons across while swimming the stock. Rosella wrote about one such river crossing where it took the men and older boys a week just to cut and haul enough trees for the rafts.

Six long months after leaving Kansas the Orcutt wagon train reached Tacoma, but that was too late. They were coming as fast as possible to see their mother but Pamelia died before her children could arrive, and so did her daughter, Clarenda. Both women are buried in a family plot at Tacoma Cemetery.

Rosella reported her sixty seven year old grandfather, Daniel Orcutt, was lost after the death of his wife and so Alvin, the oldest son, became the family’s new leader. The Orcutt clan now numbered twenty seven and Alvin lead them east; away from Tacoma to the Puyallup Valley they had been reading about for twelve years, only to find all the homesteads had long ago been taken. Continuing east and looking for a place to settle the family passed through the town of Sumner and just kept going. Five miles later they reached Lake Tapps and, according to Rosella, Alvin announced “This is it!”

Alvin bought eighty acres of land from the railroad, as did Hezekiah and Tom Pixley. When Darwin and old Daniel filed with the government for 160 acre homesteads each the Orcutt clan owned five hundred and sixty acres of beautiful meadow and timber right on the shores of Lake Tapps.

The Orcutt family and others built a community alongside the lake, but that is a story yet to come.

I don’t want to just find my ancestors; I want to discover their life stories and maybe unwind a few family mysteries along the way. Ancestry.com is great for identifying those long dead relatives, but sometimes the best information is not on line at all, sometimes you have to go looking for an original document in a courthouse or church. I love that kind of search, where my reward is finding a document that has been untouched for over a hundred years.

I don’t want to just find my ancestors; I want to discover their life stories and maybe unwind a few family mysteries along the way. Ancestry.com is great for identifying those long dead relatives, but sometimes the best information is not on line at all, sometimes you have to go looking for an original document in a courthouse or church. I love that kind of search, where my reward is finding a document that has been untouched for over a hundred years.

Recent Comments